25th Feb 2025

Feminist Retrospectives: Third-wave Feminism

Feminist Retrospectives: Third-wave Feminism

We’ve made it to the third wave! Welcome back to our series of blogs which contemplate the aims, objectives, and outcomes of different periods of feminism. Due to GGC’s vested interest in gender equality, we thought one of the best ways to help accomplish this was through a critical understanding of women’s political history: the way notions of ‘man’, ‘woman’, and ‘gender’ have changed across time and subcultures. We’re additionally interested in the flaws of each period, so we can look to grow and learn from the past.

As we begin to approach the modern day, we can begin to draw a lineage of different models of feminist thought and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses.

What is third-wave feminism?

Feminism’s third wave rises directly out of the ongoing discussions around de facto gender inequality and in particular the social, political, and economic structures that inhibit women’s happiness and freedoms. As such, starting in the 1990s, the movement began to ally itself more closely with other political and intellectual movements, such as sex positivity, ecofeminism, transfeminism, and poststructuralist gender theory. This was not universal, however, and bitter debates between feminists about key critical issues – such as sex work and pornography – resulted in the fracturing of feminist groups and thinkers.

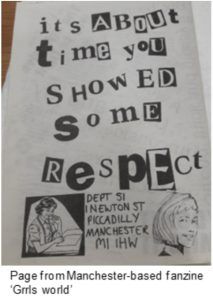

Culturally, third-wave feminism finds itself strongly articulated through Riot Grrrl punk music, as well as its accompanying zine and DIY subcultures. Self-published zines (and later, e-zines) were a way for fans to spread the word and celebrate Riot Grrrl bands, as well as opportunities to contribute to feminist discourse with personal stories, alternative (and especially ironic) models of femininity, criticisms of sexist pop culture, and fantasies of a liberated future for women.

The term ‘third-wave’ comes from an article in the US-based feminist magazine Ms., an impassioned piece by Rebecca Walker that condemns the nomination of a Supreme Court judge who had been accused of sexual harassment. She wrote:

Let this dismissal of a woman’s experience move you to anger. Turn that outrage into political power. Do not vote for them unless they work for us. Do not have sex with them, do not break bread with them, do not nurture them if they don’t prioritize our freedom to control our bodies and our lives. I am not a post-feminism feminist. I am the Third Wave.

If this strikes a chord today with the #MeToo movement, then this foreshadows that fourth-wave feminism is largely a continuation of third-wave feminism, much in the same way that third-wave is a continuation of the second. Many of the key concepts found in third-wave will come up again in the fourth wave, just with new contexts (particularly, the rise of online misogynistic harassment) to deal with.

Why did it come about?

There is not really much time between second-wave and third-wave feminism, as the third wave felt that the aims of the second were unfinished. Despite legal successes and the establishment of feminist institutions (such as rape crisis and domestic abuse shelters), third-wave feminists felt there were still many derogatory and disrespectful depictions of women in pop culture that impeded their advancement in the public sphere. They also questioned whether the sexual emancipation resulting from the second wave, made possible in improvements to contraceptive technology, fully considered women’s consent and bodily autonomy in sexual relationships. Certainly, as we saw with the above judge being nominated to the Supreme Court despite sexual harassment claims, the casualisation of sexual violence remained a problem.

Due to the implementation of women’s studies and gender studies courses at universities during the second wave, third-wave feminism was largely informed by academic shifts towards poststructuralism. Largely epistemological, poststructuralism describes a shift toward understanding meaning as fluid, culturally inherited, and socially reinforced. The implications for gender were that concepts like ‘man’, ‘woman’, ‘male’, and ‘female’ began to be understood as social constructs, meaning they have no inherent meaning beyond what we collectively understand them to be. Further, these meanings are enforced through our expectations and regulations of what constitutes acceptable gendered behaviour. The most enduring scholar of poststructuralist feminism, Judith Butler, notes in their ground-breaking 1990 text Gender Trouble:

[G]ender is not to culture as sex is to nature; gender is also the discursive/cultural means by which “sexed nature” or “a natural sex” is produced and established as “prediscursive,” prior to culture, a politically neutral surface on which culture acts.

Poststructuralists pointed out that the notions of ‘biological sex’ and ‘biological differences’ between genders which justify misogynistic reasoning are no more than cultural constructs. The meanings of biological sex (often conflated with gender) operate around not a strict ontological truth about either gender or sex, but the disparity in power between men and women. In other words, poststructuralism asks the pertinent questions: who decides what makes a ‘man’, and who decides what makes a ‘woman’? Generally, it has been the white male intellectual tradition that has had cultural dominance in defining and making assumptions about these terms.

In line with poststructuralism’s emphasis on the role white male power plays in controlling gender’s meanings, the third wave was also an attempt to address and reconcile previous waves’ neglect of non-white and working-class women. Activist and professor Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw developed her notion of ‘intersectionality’ as a model for future feminists to consider how the intersections between race, class, and gender relate to the power structures that inhibit women’s freedoms. This has helped us understand, for instance, how black women are especially sexualised; this is due to a historical tradition of sexual violence against slaves, which was in turn justified by slave owners’ beliefs that black women are inherently more ‘bestial’, ‘uncivilised’, and sexually insatiable. This racist idea comes from an older Christian belief of ‘the excessive sexuality of blacks’, an idea that ‘was encouraged by the widespread belief in the legend that blacks were descendants of Ham in the Genesis story, punished by their sexual excess of their blackness.’ It was further perpetuated by colonists when they encountered non-monogamous societies in the New World. Understanding the legacy of these racial and gender constructs has given greater awareness of the increased risks and struggles faced by black survivors of sexual violence.

What can we learn from third-wave feminism?

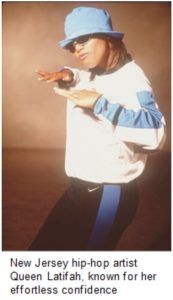

Third-wave feminism helped to completely open up what it means to be a woman, and provided many alternative ways to express femininity and womanhood. For instance, femininity was morphed and redefined into something strong, assertive, and powerful; Riot Grrrls’ adoption of ‘baby girl’ aesthetics and punk rock’s raucous and disruptive stylings were just one instance of women expressing femininity in contrast to its traditional cultural meanings of weakness, frailty, and dependence. Elsewhere, we began to see greater representation of black female artists such as Queen Latifah and Mary J. Blige who, in their own unique ways, contributed to the variety of feminine expression and presented strong, iconic, and confident versions of womanhood. Realising that gender could be moulded, that it was a series of decisions and expressions rather than simple biological determinism, had (and still has) an emancipatory impact on women.

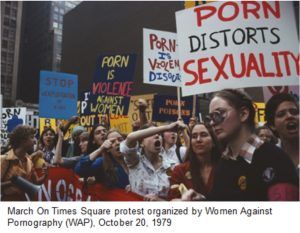

Mostly, third-wave feminism suffered from fracturing. Sex-positive feminists argued with anti-porn feminists about whether pornography should be banned due to its degrading depiction of women, or whether pornography can change to accommodate the need for consent to be depicted and the importance of female sexual pleasure. This could result in some strange alliances, with anti-porn feminists such as Andrea Dworkins and Catherine MacKinnon pairing up with right-wing groups to pass anti-porn ordinances in a number of US cities. Today, debates about the rights of sex workers represent a similar split between sex-positive feminists and feminists concerned with more stringently dismantling certain structures which they see as inherently patriarchal.

Third-wave feminism would also set the stage for bitter disputes between anti-trans ‘feminists’ (there is contemporary debate about whether they should be called feminists) and feminists seeking liberation for transgender people. In particular, Germaine Greer would set the precedent for TERFs (trans-exclusionary radical feminists) to insist that trans women are ‘invading’ cis women’s spaces, all-the-while erasing the similar experiences of misogyny trans women face. TERFs would go on to emphasise a strictly biological definition of womanhood for their political ends (problematic in itself, as many trans people medically change their bodies), reversing the important work of poststructuralist feminism to liberate gender and sex from biological determinism.

Much like previous waves, what these fractures represent is a misunderstanding of the needs of different types of women, be them porn actresses, sex workers, or trans women. As we move into next week to consider fourth-wave feminism, where many of these fractures still exist, we will again turn to inclusivity, and consider and learn from different women’s voices.

List of image sources:

From ‘Grrrls world’, The Women’s Library at London School of Economics Special Collections zines archive [photo taken by author]

From ‘Rebel grrrl Punk #6’, The Women’s Library at London School of Economics Special Collections zines archive [photo taken by author]

https://thequietus.com/articles/22119-x-ray-spex-subject-of-new-documentary

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-et-bio-qlatifah-pg-photogallery.html

Barbara Alper/Getty Images (image taken from here: https://bostonreview.net/articles/me-too-deja-vu/)