20th Feb 2025

Feminist Retrospectives: Second-wave Feminism

Feminist Retrospectives: Second-wave Feminism

Welcome back to our series of retrospective blogs, in which we contemplate the aims, objectives, and outcomes of different periods of feminism. GGC has a vested interest in gender equality and empowering women; we hope to help achieve this through a thorough and critical understanding of women’s political history. This includes the way notions of ‘man’, ‘woman’, and ‘gender’ have changed across time and subcultures, as well as the flaws of each period. As a consequence, we hope to establish a feminist network committed to inclusivity and gender liberation.

The second-wave is significant for GGC because it is during this movement that female-only consciousness raising groups were established, which parallels our own aims of it being a conscious raising group regarding gendered issues.

What is second-wave feminism?

This second wave of feminist activity, with hotspots in the UK, US, and Europe, began in the early 1960s and continued into the ‘70s and ‘80s. The term ‘second-wave feminism’ was popularised in the late ‘60s, thanks to a 1968 New York Times Magazine article titled ‘The Second Feminist Wave: What do These Women Want?’, written by journalist Martha Lear. In it, she wrote: ‘Proponents call it the Second Feminist Wave, the first having ebbed after the glorious victory of suffrage and disappeared, finally, into the great sandbar of Togetherness.’

Whereas first-wave feminism’s legacy was to gain the right to vote for women, second-wave feminism broadened its outlook towards more de facto forms of sexist discrimination, providing the basis for understanding societal issues – such as division of wealth and labour, domestic violence, marital rape, and reproductive rights – in explicitly gendered terms. It also sought to structurally change the support available to women by establishing rape crisis centres and women’s shelters.

There were also legal focuses such as establishing custody laws that support survivors of abuse, as well as fighting for no-fault divorce (before this law came into effect, married couples had to bring evidence to a court of law to prove marital disfunction, such as photos of infidelity). The latter was important in freeing women from abusive relationships where evidence was difficult to provide (e.g., physiological abuse) or where courts turned a blind eye to physical abuse. This is especially the case with marital rape, which was not legally understood as spousal violence as it has traditionally been seen that it is a wife’s duty to be sexually available to her husband. In the UK, it would not be until much later in 1991 that a husband was convicted of marital rape in a landmark trial. Finally in 2003, marital rape was explicitly outlawed under the Sexual Offences Act.

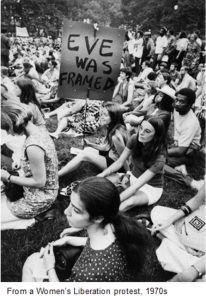

Second-wave feminism was expansive in its objectives, because it questioned the very structuring of women’s lives. It interrogated women’s relegation to specific jobs and duties such as child-rearing, domestic labour, and low-paid work, and as such inspired the slogan: ‘The personal is political.’ It drew connections between women’s specific experiences and the broader social and economic structures that at worse, enabled gendered violence against them, and at best, still reflected their lack of agency, representation, and participation.

Why did second-wave feminism happen?

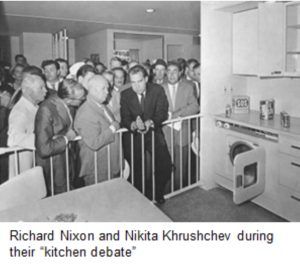

The end of World War II brought with it a plethora of global changes: with far greater numbers of casualties than any war prior – including huge numbers of civilian deaths – nations sought to rebuild in the war’s aftermath. Buildings that had endured bombings obviously needed replaced, but further, there was a desire to rebuild populations through strict enforcement of heteronormative notions of ‘family’. In Western Europe and the US, families were ideally structured centred around a new post-war threat: the expansion of communism. As the USSR rolled tanks into Eastern Europe and forcibly installed communist regimes, they brought with them an alternative vision of soviet women as comrades in arms rather than housewives or sex objects. Thus, the ‘nuclear family’ was forged, one reflected capitalist ideals of prosperity, suburban life, gendered division of labour, and heteronormative reproduction. As historians such as Elaine Tyler May have argued, strict gender roles were enforced as the ‘home’ became a battleground for keeping communist values at bay.

Nowhere was this more epitomised than US Vice President Richard Nixon and USSR General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev’s famous ‘kitchen debate’ from 1959, in which the two argued over the ideal set-up of domestic affairs. “We have many different manufacturers and many different kinds of washing machines so that housewives have a choice”, Nixon declared. This reveals the normative role of women as housewives, in charge of domestic labour, which was built around a new market of ‘white goods’ (e.g., washing machines, fridges, freezers, microwaves, etc.) that had developed in the prosperity of the post-war era.

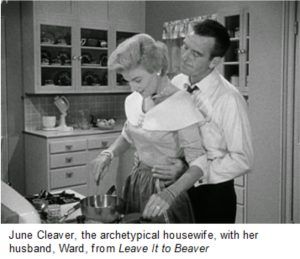

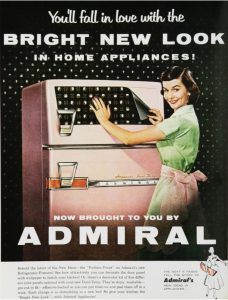

The ideal woman was reflected in sitcoms and TV shows of the time, including the character June Cleaver of Leave It to Beaver fame. Her character epitomised the ideal: married, careerless (being a housewife instead), heterosexual, child-oriented, submissive to the authority of her husband, chaste, but also, contradictorily, physically attractive and desirable. Such was June Cleaver’s commitment to feminine attractiveness that even in scenes of her gardening, she is wearing make-up, a pearl necklace, and a classic 1950s ankle-length dress. Strict enforcement of feminine presentation for housewives partly came from American journalists being mortified at the desexualisation of soviet women, who reported that because they had jobs outside the home (often in factories) they were “unconcerned about their looks” and “unfree” to be the kind of woman the American ideal prescribed.

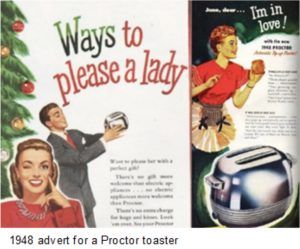

The irony, of course, is that this construction of femininity was incredibly restrictive and completely undermined women’s authority and subjectivity. For instance, despite being in charge of the home, it was June’s husband, Ward Cleaver, who brought discipline and order to the house, especially when the children misbehaved. The result was that women were idealised mostly as quiet domestic servants more than being in charge of the domain they had been relegated to. June’s character was also written to be generally meek and opinionless, a result of the construction of women at this time as intellectually inferior and therefore more child-like. This was reflected in 1950s advertising, too, which depicted housewives gasping in infantile wonder at cleaning products or white goods. In the UK, a similar sitcom called ‘The Grove Family’ reflected this ideal for women, though it was admittedly more austere as the UK took longer to economically recover from the war, with fewer pearl necklaces and white goods on display. But the overarching theme of women’s prescribed meekness and domesticity remained.

Second-wave feminists responded that this ideal was not only restrictive, confining women to a submissive life of unpaid domestic labour, but not representative of women’s ambitions, capabilities, intelligence, power, and desires. In fact, a book published in 1994 that documents the diverse lives, interests, and pursuits of post-war women is called Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945-1960. It tells of the various ways women began becoming involved in activism in spite of or because of the mainstream depiction of women as powerless and consigned to the domestic sphere.

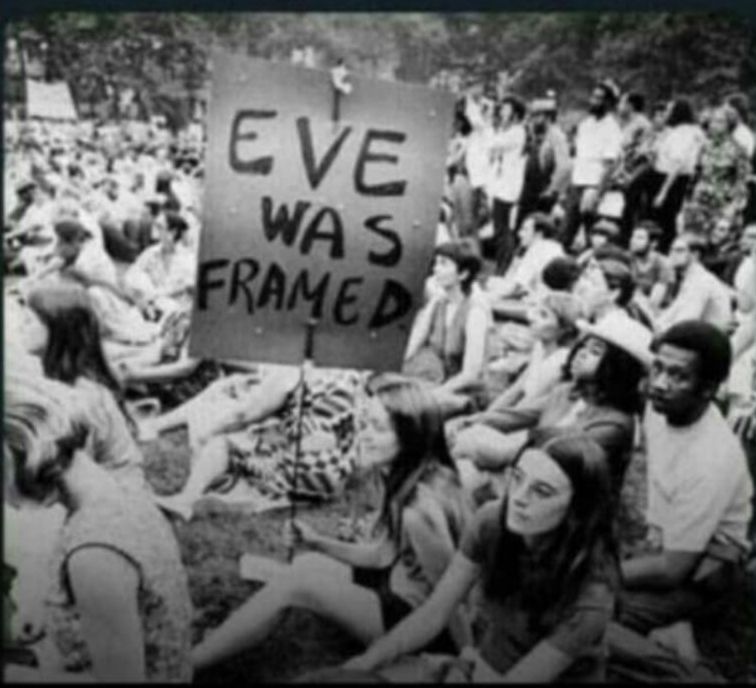

Another key factor was the introduction of new types of birth control, most importantly the hormonal contraceptive pill. Although contraception had been invented before the war, such as condoms and diaphragms, they were reserved exclusively for married couples, and generally it was the husband who took control of that aspect of family life, as it was seen as unbefitting of a wife to think about and plan sexual matters. The pill, however, had to be taken by women to work, and it was easier to take in case a sexual opportunity arose than say, having to put a diaphragm in before sex. This allowed for much greater sexual freedom for women which in turn helped them dismantle the restrictive sexual mores placed on them, and fight against the expectation of chastity. For instance, the pill facilitated the sexual revolutions of the 1960s, in which women and a broader student and hippy movement protested the wars fuelled by Cold War doctrine, the nuclear family, rigidly defined gender roles, and more.

What can we learn from second-wave feminism?

Because it was so broad in its aims, second-wave feminism achieved creating an unprecedented atmosphere for critique and liberation regarding gendered issues. It retains some of the issues of first-wave feminism in that the perspectives heard and recorded were more often white middle-class women. Generally, non-white women activists allied themselves more closely to race-based civil rights movements, and it was not until later that black feminists would have the official space to talk about how race and gender intersect. For instance, it was in 1989 that professor Kimberlé Crimshaw coined the word intersectionality to describe what it means to be both black and a woman in the face of the dual forces of white supremacist and patriarchal structures.

The historical narratives of second-wave feminism also tend to centre very firmly on the development of contraceptive technology (especially the pill), which while important, demonstrates the biases towards heterosexual women rather than the equally important and overlapping gay liberation movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s. These movements too played an immensely important role in dismantling rigid gender roles, criticising the nuclear family, and protesting the heteronormativity of capitalist ideals. As poet and essayist Adrienne Rich notes in her foreword to Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence, homosexual erasure is ‘an erasure which I felt (and feel) to be not just anti-lesbian, but anti-feminist in its consequences, and to distort the experience of heterosexual women as well. […] I continue to think that heterosexual feminists will draw political strength for change from taking a critical stance toward the ideology which demands heterosexuality.’7 For brevity’s sake, the discussion of gay liberation will unfortunately have to end here, but it is worth mentioning especially in light of the role queerness will play in later waves of feminism.

One of the most important legacies of second-wave feminism for our current context was the development of ecofeminism, which saw women and academics working with newly popular strains of environmentalist thinking that began seeing prominence during the 1970s. Although conclusions vary about women’s “natural” role in promoting ecological thinking, certainly the construction of women as somehow more subjugated by their biology (due to menstruation, pregnancy, and child birth) encouraged women to think about human relationships to the planet, as well as the artificial divisions between culture and nature. Ecofeminist thought would be expanded upon in the third and fourth waves, and has played an important role in critiquing masculinist modes of relating to the Earth, favouring respect, co-operation, nurture, and inclusion over domination, objectification, and destruction of non-human life.

Retrospectively, the biggest lesson to learn is perhaps the importance of feminist unity, and the immense upheaval of cultural misogyny it can achieve. While there were always feminist debates and differences within the movements, it was really towards the end of the 1980s that feminist groups began to split off over key issues such as sex work and pornography. If in 1968 Martha Lear described second-wave feminism as ‘a great sandbar of Togetherness’, this feeling did not last. As different groups’ aims became contradictory, in-fighting became more bitter; and this leads us up to next week’s blog on third-wave feminism.

Thank you very much for reading and tune in next week for our next instalment of feminist retrospectives.

Image sources:

Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era by Elaine Tyler May (New York: Basic Books, 2008), p. 20

http://solidmoonlight.blogspot.com/2015/05/junes-dresses-in-leave-it-to-beaver.html

http://copyranter.blogspot.com/2014/09/according-to-advertising-1950s-woman.html

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/441493569704039901/

https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/gabrielsanchez/lgbt-history-pictures-gay-liberation-stonewall

https://econscholaruon.wordpress.com/2020/06/09/eve-was-framed-and-the-white-house-burnt-down/