27th Feb 2025

Feminist Retrospectives: Fourth-wave Feminism

Feminist Retrospectives: Fourth-wave Feminism

Hello, welcome back; we’ve made it to the here and now. Although GGC is very much inspired by second-wave feminism and its monumental gestures towards the consciousness-raising of gendered issues, we’re equally drawn to current modes of feminist thinking and activism. Gender equality, inclusivity, and intersectionality have been and remain our key themes for this series on each wave of feminism. As we analyse current trends we will continue to bear in mind: whose voices are omitted from the conversation? And what can we do to change that?

Fourth-wave feminism is one of the most diverse waves yet, with differing views on a multitude of issues including trans rights, sex work, and the role of women in capitalist ventures. It is a difficult wave to characterise for this reason, and also because we are living through it. It will be difficult to know what fourth-wave feminism’s legacy will be, but equally we have the power to mould it.

What is happening in fourth-wave feminism?

This wave is a little difficult and arbitrary to date, as third-wave feminism bleeds in significantly to discussions relevant to today’s context: be it online misogyny, the hyper-sexualisation of female bodies, the ongoing lack of representation of women in positions of power, and the need for a feminist approach to ecology and the climate crisis. However, what distinguishes it from previous waves is the media which feminists use to convey their message. Social media more than ever presents a powerful tool to spread feminist awareness, to research and debunk anti-feminist and transphobic claims, and to connect together women’s stories to illustrate the extent of systematic sexism.

Some commentators date the start of fourth-wave feminism as 2012, when a series of high-profile incidences of sexual violence – including an infamous assault by multiple men in India, where the victim later died from her injuries – sparked international outrage. It was a story that made its way quickly to online platforms, horrific details and all, and which contributed to a long list of similar acts of extreme misogynistic violence around the world. The ongoing problem of gendered violence, and the exhausting anger of having the same conversations about it only for it to happen over and over, remain a theme of feminist discourse today.

Realising the internet was a powerful tool, feminist critics began to pop up on platforms such as YouTube to tackle a range of topics: from rape culture to media and video game criticism, there had never before been so much feminist content online. And yet, as Susan Faludi could have predicted (author of the feminist classic Backlash), there was a massively reactionary response to this so-called ‘social justice warrior’ movement. The young men who had up until this point dominated gaming circles and online forums including YouTube (but also 4Chan and Reddit) unleashed a tide of fury at creators such as Anita Sarkeesian, in what became known as ‘Gamergate’ and which evolved into today’s Men’s Rights Movement. Sarkeesian became the primary target for this outrage, since she was known for her criticisms of video games that overly sexualised its female characters. Interestingly, less often do her critics consider her videos where she celebrates strong and diverse representation in other video games, instead preferring to characterise her as a buzz-kill or a “nag”. The harassment campaign gamers carried out against her and others escalated to threats of violence and rape. Despite this, anti-social justice warrior content continued to see popularity. Just one example are the viral “feminist cringe” videos – still available on YouTube today – in which commentators mock women who are speaking passionately, angrily, and sometimes ineloquently about gender inequality. The idea behind the videos is for male commentors to laugh and claim their arguments are exaggerated, or alternatively they simply frame the women’s anger (even if it is justified) as confirming their prejudices that women are “too emotional” to be making political arguments. The legacy of online anti-feminism lives on in forums today such as the subreddits /r/MensRights and /r/MGTOW (which stands for ‘men going their own way’), which dishonestly frame feminism as a force which threatens men’s liberation from the pressures of normative gender roles.

Yet feminist issues remained prominent online as massive news stories of men in powerful positions assaulting women came to light. Whether it was Trump bragging about sexual assault or the multitude of allegations against Harvey Weinstein, whose behaviour was not even a secret within the movie industry, the news presented overwhelming evidence of systemic violence against women. This culminated in the #MeToo movement, beginning in 2006 but exploding in 2017, where women from a multitude of backgrounds and from across the globe shared their stories of sexual harassment and/or assault online, as well as the disbelief, blame, or inaction they were often met with. The idea behind the movement was to speak out and bring culpability to sexual offenders, especially high-profile ones, and to further the conversation around how to best support survivors.

In the context of ongoing misogynistic violence, and the influence of degrading images of women made readily available through mainstream porn, prominent women have expressed their struggles with asserting their sexuality. Some, including Billie Eilish, whose youth is certainly a factor, have very publicly spoken about the decision to dress deliberately in baggy, desexualised clothing in part as a response to the extreme pornographic images she was exposed to as a young teenager. Meanwhile, women like Megan Thee Stallion and Cardi B feel that playing into their hyper-sexualisation – and crucially, monetising it – empowers them, arguing they are in control. Certainly their song ‘WAP’ made headlines from conversative media outlets shaming their overt sexuality while more left-wing media generally celebrated the song as a bold expression of sexual desire from the female perspective.

Meanwhile, the minority voices of certain third-wave feminists and lesbian activists that reject the advancement of civil rights for trans people have now joined together with transphobes of all political backgrounds. Known as TERFs (trans-exclusive radical feminists) or sometimes euphemised as ‘gender critical’, they have gained prominence most recently due to a few key celebrities forwarding their arguments, most notoriously J. K. Rowling (author of one of the biggest children’s series of books ever created, the Harry Potter series). Misinformation around trans women assaulting cis women in public bathrooms and prisons (when the reversal is more likely to be true, as trans people are at a much higher risk of physical or sexual abuse) have fuelled decisions to halt or reverse the advancement of trans rights. Again, queer and trans people benefit immensely from online spaces that include and support them, but equally suffer similar kinds of harassment and abuse, especially if they decide to become more public-facing in their field or in activism.

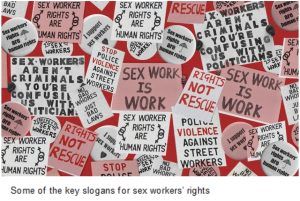

Similarly controversial, the fight for sex workers rights has taken on a whole new surge of energy in the fourth wave. Comedian Sara Pascoe’s book Sex Power Money and her accompanying podcast of the same title highlights and details some of the key arguments from sex workers about the best way to secure their rights and prevent their exploitation and abuse. Contemporary discussions around police brutality have intersected strongly with sex workers’ experiences, who, when subjected to physical and sexual abuse by police officers, have no means of legal recourse. The fight for legalisation of sex work is ongoing, but increasingly we are gaining access into the lives and perspectives of sex workers themselves during the fourth wave.

Workers’ rights, including the rights of sex workers, have gained prominence in public discourses as capitalist structures continue to widen economic inequalities, and which have only been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. The role of women within capitalism has become a key point of contention and critique in feminist discourse, including the adoption or renunciation of the terms ‘girl boss’ and ‘she-e-o’. Girl boss feminism argues for better opportunities for women to be in top positions in various existing power structures, be it politics, private companies, judiciaries, the police, and more. On the other hand, anti-capitalist feminists note that it is not the fact that there are few women in positions of power that’s a problem, but that these power structures themselves are exploitative. For instance, they point out that global poverty is gendered, as workers involved in making cheap commodities and fast fashion are usually women in the global South, with working conditions that are not only inhumane but which allow sexual exploitation by male overseers. There is no guarantee that a female CEO would put an end to this if companies’ primary vision is to continue making massive profits, and indeed, women can just as easily abuse positions of power as men should they attain them. How to empower women in the complex matrix of capitalist exploitation that has gendered implications across the globe remains a contradiction.

What does fourth-wave feminism mean to us now?

Feminist analysis from the years 2012 to the present feels bleak. The advent of the internet was as much of a bane to feminist discourse as it was a boon. Certainly, the connectivity women felt was unprecedented. In the graphic novel Becoming Unbecoming by Una, an autobiographical work which details the sexual exploitation of schoolgirls and women in England in the ‘70s, the author notes that coming online into the 2010s was a massive moment for survivors, who could share stories, support one another, and fight for better treatment. But equally, online forums promoting misogyny and transphobia have only strengthened.

On the other hand, an emerging culture on YouTube providing leftist critiques on a broad range of topics – from the philosophy of Jean Baudrillard in The Matrix to addressing non-scientific alt-right claims that a vegan diet is ‘feminising’ modern men – have cultivated an atmosphere of critical thought that help dismantle anti-feminist and alt-right talking points. Known as ‘BreadTube’, key creators include: hbomberguy, who flipped the “feminist cringe” videos on their head by mocking alt-right content creators; Contrapoints, a trans woman and ex-postgraduate student in philosophy who has helped convert alt-righters and popularise key arguments for trans liberation; and a plethora of other creators and collaborators such as PhilosophyTube, Lindsay Ellis, Kat Blaque, Folding Ideas, Sarah Z, Shaun, and many more.

What the fourth wave is currently showing us is that long fought-for rights cannot be taken for granted. In the US, women are dealing with attempts to reverse abortion rights, with Texas outright banning abortion in May 2021. In the UK, one woman is murdered every three days, a statistic that has made headlines since the murders of Sarah Everard and Sabina Ness have come to light. More and more, feminist perspectives are offering the view that narratives of linear social progress are from the extremely narrow perspective of the privileged, who do not have to deal with their safety and bodily autonomy being threatened by a combination of people and increasingly right-wing state authorities.

Furthermore, while ecofeminists offer alternatives to the masculinist modes of existence that have dominated our interactions with the earth, including models of mutual giving, care, nurture, and granting respect and political rights to non-human life, the ideas and concepts are mostly restricted to academia. As co-author of the influential Ecofeminism Vandana Shiva writes in the preface to the critique influence change edition: ‘When Maria Mies and I wrote Ecofeminism two decades ago, we were addressing the emerging challenges of our times. Every threat we identified has grown deeper. And with it has grown the relevance of an alternative to capitalist patriarchy if humanity and the diverse species with which we share the planet are to survive.’1 The book is endlessly insightful, and yet these conversations have mostly been side-lined due to the more immediate threat that right-wing governments pose to women’s bodily autonomy.

As we move forward, the question of inclusion is not just a philosophical one, but an existential one. To be a feminist today means to fight for the rights of marginalised groups, be them sex workers, trans women, or non-humans whose ecosystems have been disrupted. These alliances are crucial in our current context of the climate crisis because it is exactly this kind of fracturing that is detracting. This is not a call to tolerate TERF arguments, but to stay informed, be vigilant, and know that an intersectional feminism is the most empowering for us all.

Thank you for joining us in this series of blogs. Watch this space for future blogs with a more specific focus on Glaswegian feminism through each wave as we continue to explore different journeys of feminist activism.

Image sources:

https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/2018/10/13/metoo-impact-hashtag-made-online/1633570002/

https://www.popbuzz.com/music/artists/billie-eilish/news/baggy-clothes-body-interview/

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/christian-right-feminists-uk-trans-rights/

https://www.huckmag.com/perspectives/reportage-2/the-rights-of-uk-sex-workers-are-under-threat-why/

https://csusmchronicle.com/21688/opinion/girl-boss-feminism-symbolizes-regressive-gender-politics/

Becoming Unbecoming by Una [North American edition] (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016), p. 117

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ity8CVCk2VQ [image taken from thumbnail]