18th Feb 2025

Feminist Retrospectives: First-wave Feminism

Hello and welcome to the first of our series of blogs which contemplate the aims, objectives, and outcomes of different periods of feminism. Here at GGC, we have a vested interest in gender equality and empowering women. One of the best ways to help accomplish these aims is through a thorough and critical understanding of women’s political history; the way notions of ‘man’, ‘woman’, and ‘gender’ have changed across time and subcultures; as well as the flaws of each period, so we can look to grow and learn from the past.

First-wave feminism is a great place to start, not only chronologically, but because there are immense opportunities to learn from its mistakes.

What is first-wave feminism?

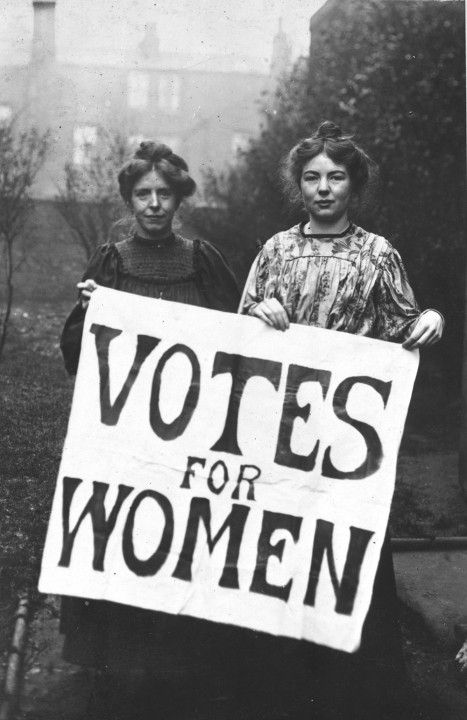

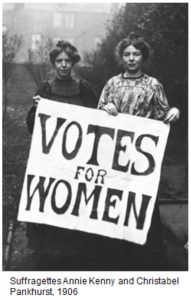

Starting roughly in the 19th century and picking up traction and legal successes in the early 20th century, first-wave feminism describes a simultaneity of movements across Europe, Britain, and North America. Its focus was primarily legal: its advocates fought to secure civil and political rights and in particular, the right for women to vote. As a political collective these women were known as suffragettes, arguably a diminutive title, and they fought long, hard, and across generations to secure the right to vote.

Starting roughly in the 19th century and picking up traction and legal successes in the early 20th century, first-wave feminism describes a simultaneity of movements across Europe, Britain, and North America. Its focus was primarily legal: its advocates fought to secure civil and political rights and in particular, the right for women to vote. As a political collective these women were known as suffragettes, arguably a diminutive title, and they fought long, hard, and across generations to secure the right to vote.

As early as 1867, a proposal to enfranchise women was put forward to the British parliament. The proposal argued for women to be given the vote based on their equality with men; it was rejected. It would not be until 1918, after years of campaigning, hunger strikes, and even violence and vandalism, that women over the age of thirty would be allowed to vote. It would be ten years later in 1928 that this age would be lowered to match the voting age of men (twenty-one).

What prompted first-wave feminism?

Historians have offered different answers, though certainly one common historiographical element is that women’s material conditions were changing throughout the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution swept up all kinds of workers into factories in its wake, with loosely defined labour laws permitting child labour, women’s labour, and excruciatingly long work days. Although women’s jobs were still typically gendered – i.e., textile factory jobs, maids/cooks – they were engaging with public life more than ever due to their mass employment in these roles. Before, women would have largely been constrained to the domestic sphere: cooking, cleaning, and looking after the children; essentially, they were engaging in unwaged labour (and largely still do – but this is a topic for a later blog). This was reflected in Victorian language too; a ‘public woman’ was a euphemistic term for a sex worker, the implication that the only women in public spaces (without a man) were selling sex. But now, women had civic interests: they were subject to the ever-evolving labour laws that looked to improve workers’ rights and conditions; they helped mass-produce commodities and materials that would be sold to the public, creating value beyond the domestic sphere; and they were in factories with other women, where they could converse, co-ordinate, and form a sense of solidarity with one another.

As we moved into 20th century, and with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, there was a growing sense that women’s contribution to society must count for something. As historian Leslie Hume writes:

The women’s contribution to the war effort challenged the notion of women’s physical and mental inferiority and made it more difficult to maintain that women were, both by constitution and temperament, unfit to vote. If women could work in munitions factories, it seemed both ungrateful and illogical to deny them a place in the voting booth. But the vote was much more than simply a reward for war work; the point was that women’s participation in the war helped to dispel the fears that surrounded women’s entry into the public arena.

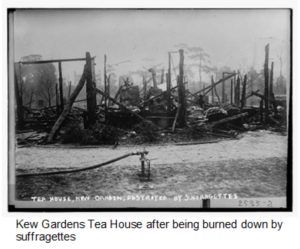

Certainly, suffragettes would adopt the methods of warfare to get their point across: for instance, when the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) set fire to David Lloyd George’s (unoccupied) house in 1913, as well as sending letter bombs; smashing windows, most (in)famously the greenhouses’ windows at Kew Gardens in London; cutting telephone lines; spitting at police; and various other acts of vandalism. Not all were violent; other organisations insisted on protesting more peacefully, including the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Its leader, Millicent Fawcett, reportedly described the women’s suffrage movement in a 1911 speech as being ‘like a glacier; slow moving but unstoppable’.

Why did it take so long?

The short answer is backlash. You could make the argument that violence impeded the cause, but pushback and mockery began well before suffragettes resorted to brick-throwing. There was staunch opposition to women’s suffrage because it threatened very rigidly defined roles and conceptions of gender.

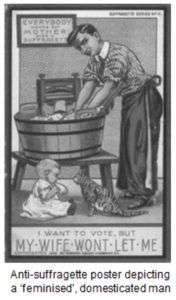

In an article by Anthony Pankuch, he notes that suffragettes across Europe and America faced criticisms of being a “third sex”. For instance, in June of 1909, Bishop William Croswell Doane of Albany, New York delivered a speech to a Catholic women’s institute where he derided suffragettes as “bearded women”, “effeminate men”, “long-haired men”, and “lusus naturae” (Latin for ‘freaks of nature’). While this is quite an extreme example, the bishop was voicing the fears of many Victorians that women’s empowerment in the public sphere disrupted a rigidly defined gender binary. If women could vote, they feared, they would take men’s places; women would be masculinised and men, feminised. This was not limited to religious beliefs, either: German psychiatrist Krafft-Ebing believed men’s “effeminacy” would lead to “moral decay” and eventually, societal collapse. In the male-dominated discourses of science and medicine, too, suffragettes were characterised as unnaturally masculine and therefore a threat to the moral fabric of society. Of particular concern were sex workers, who were stereotyped as brash and brazen in comparison to the ideal of a meek Victorian wife. The argument from anti-feminists was that ‘the best of women would shun political life and the most unprincipled would have the field to themselves’, and this was reflected in the depiction of suffragettes as aggressively kissing.

Anti-feminist postcards circulated, which capitalised on these characterisations of suffragettes as immoral, gender non-conforming “freaks”. There were a few sympathetic politicians, such as Labour MP George Lansbury, who resigned from his seat in 1912 in support of women’s enfranchisement. But largely, politicians opposed women’s suffrage, including Prime Minister H. H. Asquith. It was only after the war, with David Lloyd George taking over, that women’s suffrage became a legal reality.

What can we learn from first-wave feminism?

First-wave feminism had many noble endeavours, and the variety of collective action – from strikes to vandalism to peaceful protests – proved effective in ultimately securing the movements’ goal of enfranchising women. However, there is a growing re-examination of first-wave feminism’s intersections with race and class; sadly, for instance, our education largely whitewashes the rampant racism within the movements. Of course, not all early feminists erased racial struggles in their feminism. Cady Stanton, a feminist from pre-Civil War era US, felt that black men and white women shared a common cause: that they were both made property, the former by slavery and the latter by marriage.

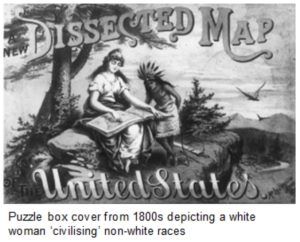

However, when racism did manifest, it was not incidental: suffragettes argued from the viewpoint of white supremacy, and used their race to codify white women as “civilised” and intelligent in comparison to their non-white counterparts. They felt their role was to be “mothers of the race”; one such example is the Women’s National Indian Association in the US, which forcefully instilled monogamous and Christian attitudes in Native American communities. They argued that non-white women could earn the right to vote if and when they adopted these “civilised” attitudes, as well as taking on traditional gender roles and wearing white styles of clothing. It was from this conception of white womanhood that suffragettes argued for their own enfranchisement at the expense of others’.

Furthermore, while the mood for the advancement of women’s rights was ripe because women were working in public spaces, we should be careful in acknowledging that its most prominent and well-remembered figures were often middle-class women rather than factory workers. This bias may be because working-class women were exhausted by their inhumanely long work days, and their opportunities for political engagement were consequently limited. It may also be because historical accounts at the time often displayed a general disinterest in the thoughts, experiences, and political endeavours of working-class women (something that is thankfully now changing in the study of history).

What next?

What these biases show is that simplified narratives of social movements can erase, ignore, or neglect the struggles of other marginalised groups. From this we can strive to do better, consider how to be intersectional and inclusive, and further social justice causes that benefit everyone. Next week, we’ll be re-examining second-wave feminism in a similar fashion. make sure to tune in and learn more about feminist history, and where to go from here.

Image sources:

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/womens-suffrage/

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Votes-For-Women/

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/outrage-at-kew/burned-suffragettes/

The Male Madonna and the Feminine Uncle Sam: Visual Argument, Icons, and Ideographs in 1909 Anti-Woman Suffrage Postcards by Catherine H. Palczewski (Quarterly Journal of Speech, 91:4, 2005), p. 372

White Women’s Rights: The Racial Origins of Feminism in the United States by Louise Michele Newman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 25